Blog

2019.06.19

Kanda

The Chiba Shusaku Narimasa Dôjô – a center for swordsmanship

Is Kenjutsu the same as Kendō?

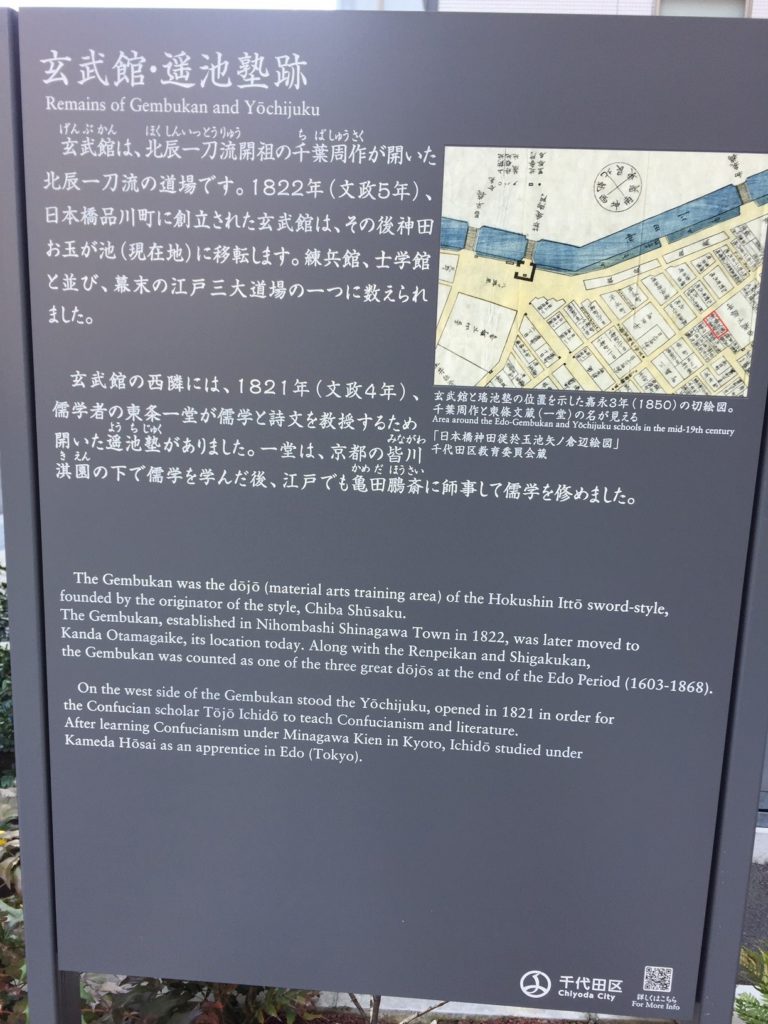

As the third part of our series of blogs about Kanda, today we’d like to introduce a location which once held a famous Dôjô of the Edo era, teaching one particular school of Kenjutsu (literally, “swordsmanship”) called Hokushin Ittō-ryū.

Nowadays when people hear the word Kenjutsu, what often comes to mind first is Kendō, but in reality the two are very different. In terms of their visual differences, kendo is practiced with one bamboo sword (called a shinai) – the katana makes no appearance. Furthermore, the primary focus of Kendō is on competition according to a set of fixed rules.

Kendo Fight (Photo by Harald Hofer/ CC BY-SA 2.0 AT)

On the other hand, the practice methods, rules, and ideologies of Kenjutsu differ substantially from school to school. There are times when practitioners employ bamboo swords, but the ultimate goal is to attain proficiency with a Katana. It’s also acceptable to wield the Katana with one hand, or with both.

A map from the Edo era. The Chiba Shusaku Narimasa Dôjô is marked in red.

The Diversity of the Katana

If we go further back in time, before the Edo era and before Kenjutsu came into its own, we find that the art was far more straightforward. The primary question was simply, how do we use the Katana effectively as a weapon? During the Sengoku era, which came before Edo, the Katana was regarded as a weapon of war. However, it is said that the weapon actually used most frequently in war was the spear. This was due to its superior reach making it advantageous over the Katana. It seems the Katana was considered a last resort in close-quarters combat. When moving close to an enemy, the blade’s length became a liability. This flaw was the impetus for the creation of a wide variety of Katana, which saw the shape and length of the swords altered.

Different types of swords (Photo by Samuraiantiqueworld/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

If we go back even further, we see that prior to the Sengoku era, the state of swords such as the katana and the Tachi (a long sword primarily used by samurai) was also quite different – however, we will save that topic for another article. Seeing as the circumstances differ so greatly from era to era, for the sake of convenience today we will limit our discussion to Kenjutsu and the Katana of the Edo era.

The Spirit and Sword of the Samurai

After the beginning of the Edo era, when battles became less and less common, Katana owned by samurai began to be standardized by the ruling Shogunate. All blades were set to a fixed length and the role of the Katana grew increasingly more superficial. Meanwhile, for the samurai of the age who prided themselves so greatly on owning a Katana that they considered the word practically synonymous with themselves, a new dilemma emerged. They had to find a meaning and purpose for the new samurai and Katana.

One answer to this dilemma was a new school of swordsmanship which featured complex choreographed movements (known as Kata), done for both practice and spiritual growth, as well as a new certification system. Before one could acquire the highest level certification in Kenjutsu, it was necessary to progress through multiple grades. These grades were seen as proof of improvement and could only be obtained if approved by the instructor.

The Logical Teaching Methodology of the Chiba Dôjô

We can use one such school, the Hokushin Ittō-ryū, to introduce a famous former Dôjô. The founder of this school was Chiba Shūsaku (born 1794). He combined three disciplines which he himself practiced into one, thereby creating the Hokushin Ittō-ryū school, and finally opening his own Dôjô, the Gembukan, near Otamagaike, Kanda. Since this was near the end of the Edo era, even the likes of Ryōma Sakamoto and other anti-shogunate samurai (known as Shishi) studied at the Gembukan.

The most characteristic aspects of this school were how it eschewed spirituality in favor of logic when it came to teaching techniques, as well as how it simplified the certification system. In addition, because it placed emphasis on training, improvement among students was quick, which led to the style gaining a lot of popularity. It eventually came to be called one of the 3 great Dôjôs of the Edo era.

It is even said that these features of being logical and centered on practice came to form the basis for modern Kendō.

Sore ken wa shunsoku – He who is faster, wins.

The straightforwardness of Chiba Shūsaku’s teachings is best expressed by something he once said, “Sore ken wa shunsoku” (figuratively translated, “the sword is but an instant”). Although the original sentence is certainly laden with deep meaning, it would be difficult to understand it for those without aspirations to master Kenjutsu. Putting it in simple terms, “he who is faster, wins.” It almost goes without saying. However, this seemingly obvious precept was revolutionary at its time. “Become nothing!” – if given such abstract instructions during training, most people would struggle to understand. However, this approach to teaching was dominant at the time. Rather than practicing “becoming nothing”, people seemed to prefer the simplistic clarity of “he who is faster, wins.”

For those with an interest in Kenjutsu, we encourage you to give the site of the former Chiba Dôjô a visit.

Leave a Reply